How To Write A Book

Behind-the-scenes of the long, meticulous and insane process of writing a non-fiction book.

Most people read books, but very few write them.

Maybe it’s because the agonising process is so mysterious, difficult and time-consuming that it would put any sane person off. I would know, I’ve written three of them so far and - in case you missed the exciting news last month - I’m currently working on my fourth.

Writing books is the hardest and most satisfying thing that I do. In the last seven years I’ve written 3.5 of them, and I’m often asked if writing books gets easier the more that you do? The honest answer is that every one feels like you’re starting from scratch, but there is one part that does benefit from repetition: the process of how it all comes together.

Every few years I pick a different topic - something big and unwieldy and knotty and uncomfortable - and spend an inordinate amount of time unpacking it. I am a curious journalist at heart, and Iove nothing more than getting to the heart of issues to help others understand them. Every few years I look at global trends and work-related pain points, then spend time researching, unpacking, interrogating experts, studying research papers and thinking to simplify complicated topics.

That’s what I’ve done so far around why some businesses succeed and others fail (Cult Status), how creativity works in a post-pandemic world (Killer Thinking), and what the future of work is (Work Backwards).

I roam the world, sit in Professor’s rooms in universities, crawl the internet, and speak to dozens and dozens of people about it. To borrow a phrase from Killer Thinking, I become the problem’s therapist.

For my fourth book, I’m tackling a topic I think is the biggest one yet. It all stems from my weekly column in the Sydney Morning Herald and The Age. Each week I focus on an interesting work and careers topic that we should be talking about more. I treat each of these as mini-experiments, tracking which receives the most reads, comments and engagements with a large audience.

The topics that typically overperform (and that I adore writing about) include:

The WFH vs Return to Office debate happening at every office water-cooler

Life/work balance that’s only become more relevant in a post-Covid world

Gen Z vs every other generation

The ongoing march of AI vs traditional ways of doing things

When you look at these topics, they all have one common thread running through them: tension. They are all about the push and pull, X vs Y, constant tug of work.

“Workplaces are built on tension,” I wrote in this story talking about the typical back and forth between how much you’re paid for work that you do and the everyday struggle between priorities and deadlines. In this story I wrote about the strain between working from home versus returning to the office.

As a curious optimist I dived into the topic of tension looking for answers. And in doing so, I came across something that I think is pretty remarkable given how little we focus on it. A lot of the research and science on tension shows that effective conflict management skills correlate almost directly with success at work and in life.

In other words, if you can learn how to be better in this one area then it’s proven to enhance workplace performance, career satisfaction and long-term interpersonal relationships. I’ve devoured study after study that shows how beneficial it is to learn how to be better in tension, yet paradoxically, most of us are terrible at it.

Now you can see why it’s such a fascinating topic.

The book will be available to read and listen to around the world in September next year with Wiley. And for this month’s Useful Thing, I’ll take you through the exact process that I use to write a non-fiction book.

Now, this might not sound immediately useful to everyone on the surface, but you can apply this thinking to any big project you’re trying to tackle.

One Useful Thing: How To Write a Book

There are 4 steps to write a non-fiction book: collect, collate, expand and arrange.

Writing a non-fiction book is as much about researching, investigating and thinking as it is about the actual words. There’s a famous quote that’s normally erroneously attributed to Abraham Lincoln: “If I only had an hour to chop down a tree, I would spend the first 45 minutes sharpening my axe.”

(On a side note: One my fave niche websites is Quote Investigator, the work of researcher Garson O’Toole who investigates the phenomenon where most of the quotes we attribute to famous people were never actually said by them. Think that Albert Einsten said “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results”? Well, he didn’t.)

I’ll start with the assumption you have an area or topic that you are thinking about. If you don’t, that’s another entire newsletter topic on its own.

Step 1: Collect

The most important skill to write a non-fiction book is curiosity. You need to question how things work, yearn to tinker with tools, have an insatiable appetite for information and want to constantly realise how little you know.

I feed my curiosity by collecting every piece of information I can into a central place.

Now, I’ve experimented with every fashionable mode for collecting information on the go, from Evernote to Notion, but I somehow keep getting pulled right back to Apple Notes as my default note taker.

I am not alone, as this meme confirms:

So now instead of fighting it, I have trained myself to use every brilliant tool hidden within Apple Notes, like tagging, to keep all my ideas in one central place.

Once you are aware of your topic, and once your senses are tuned in, everything you see becomes research. Every conversation you have, every LinkedIn post you read, every tweet you scroll past, every museum you visit, every Google or AI search, every conference you go to.

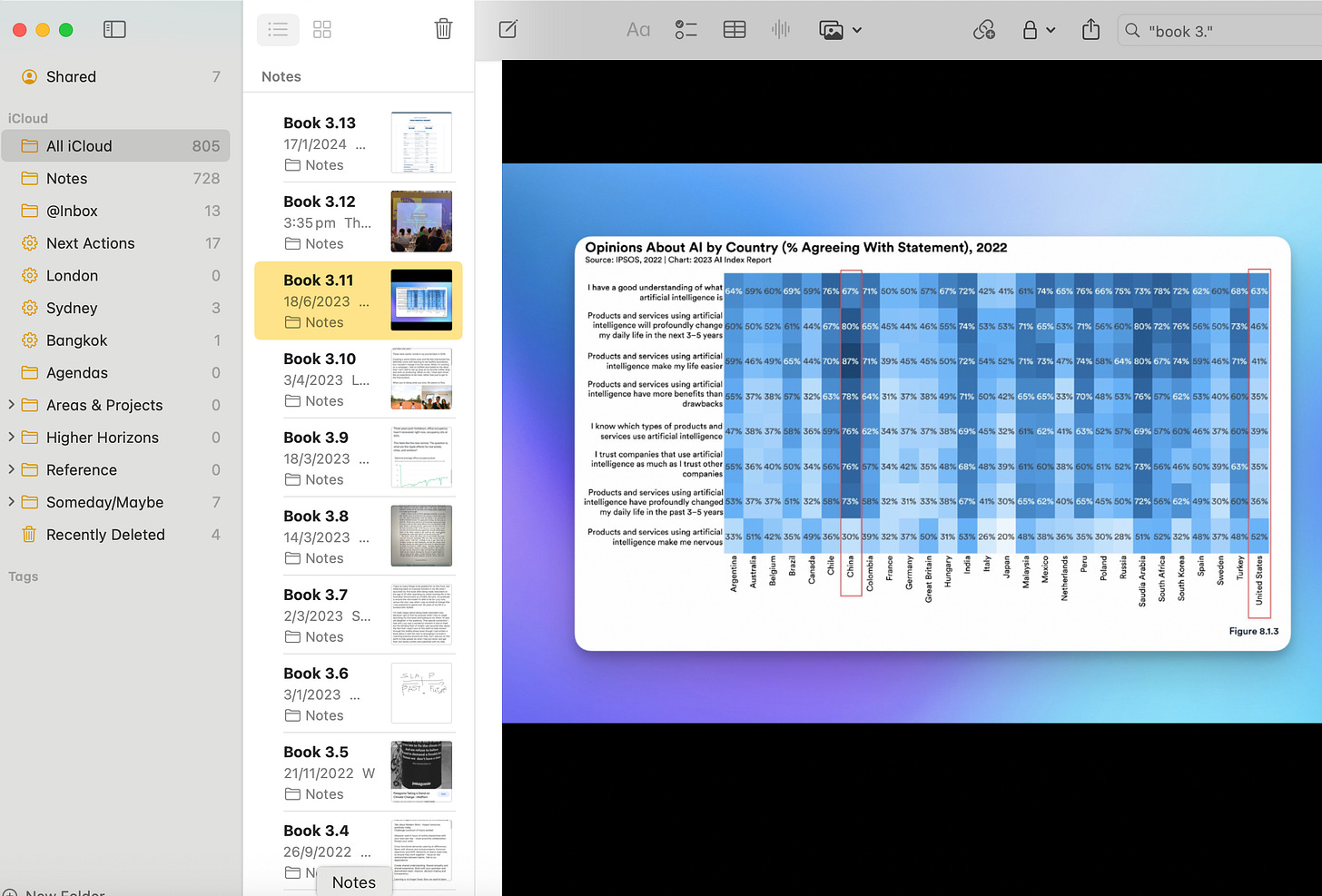

I create a note in Apple Notes on my phone titled ‘Book 3.1’ (using the example of my third book), and I add every new thought into it.

I capture every 3am thought about variations for the sub-heading, every shower idea about interviews, every sentence I have during car rides. They all go into one place until I have added so many ideas into a single Apple Note that I get sick of scrolling to get to the bottom in order to add new things in.

That is my cue to start a fresh note, titled ‘Book 3.2’, and repeat the process. Here is an example of what the Apple Notes looks like as I wrote my latest book, Work Backwards. Each ‘0.1’ of a note contains hundreds of thoughts, ideas, screenshots, photos and scribbles.

There is hardly a moment during the book writing process when I’m not contemplating the topic in some way. I even usually take a moratorium on reading fiction during these thinking periods (that’s why, as soon as I hand in a draft of the book, I celebrate and give my brain a break by devouring the latest fiction I’d been holding off!)

I consider this part of the process as behaving like a satin bowerbird. These divine birds seek out blue things - like bottle tops, feathers and plastics - and grab the items in their mouth to take them back to their nest.

I adore the bowerbird stage of writing a book.

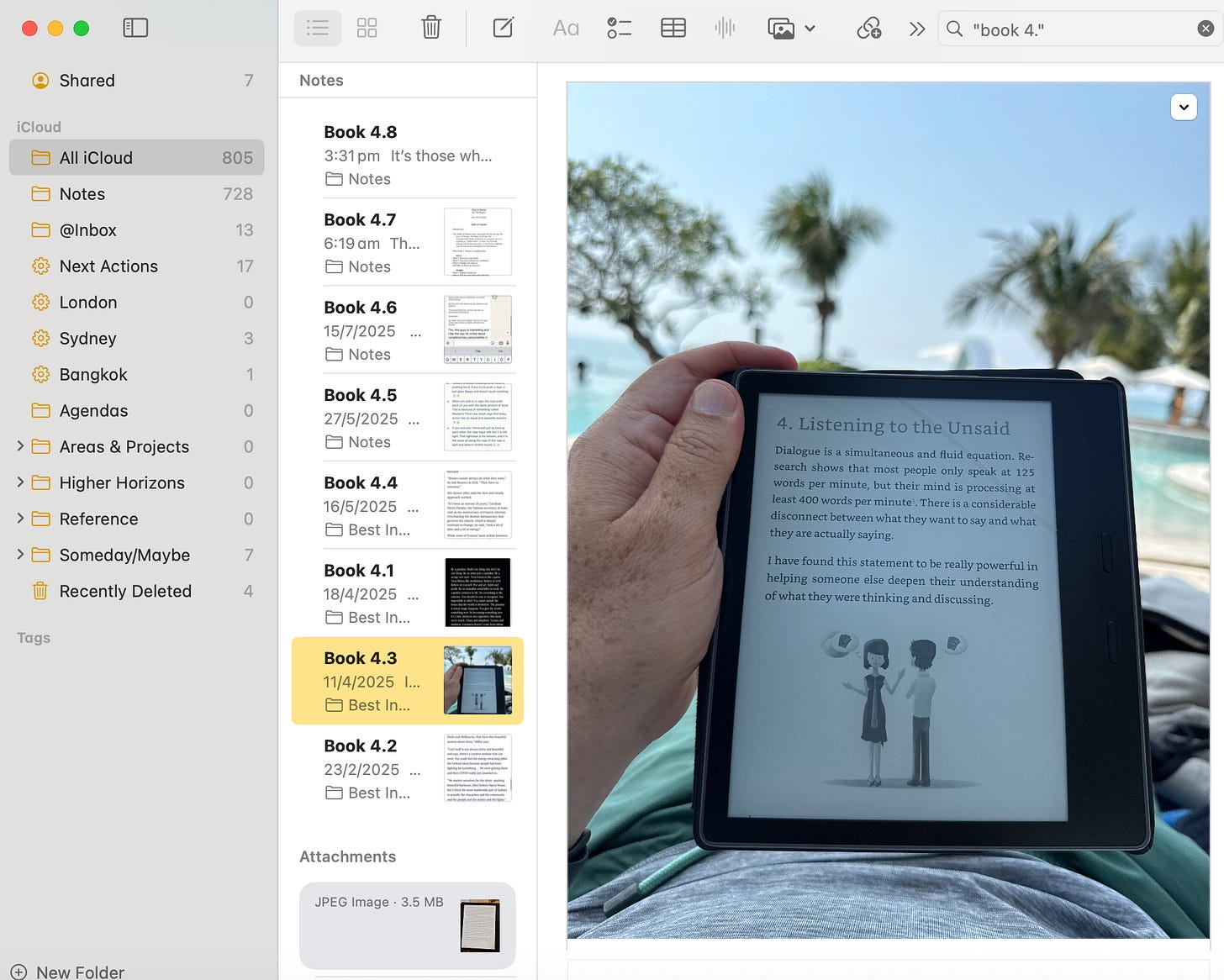

If you want a brief insight into my fourth book that I’m currently writing on tension, here’s an example of a screenshot of an interesting fact I discovered as I read by the pool. It feels like I’m only at the start of the research about conflict, and I’m already up to 4.8 in my system, meaning hundreds of fresh ideas to mull over.

Step 2: Collate

Once I’ve done some serious thinking about the topic, I take the notes I’ve collected and collate them. This means I review and unpack each of them to see if there’s anything in the thought bubbles I collected that I want to investigate further.

It often means there’s an interesting research study I need to read from beginning to end, or I try to track down the contact details for someone to interview.

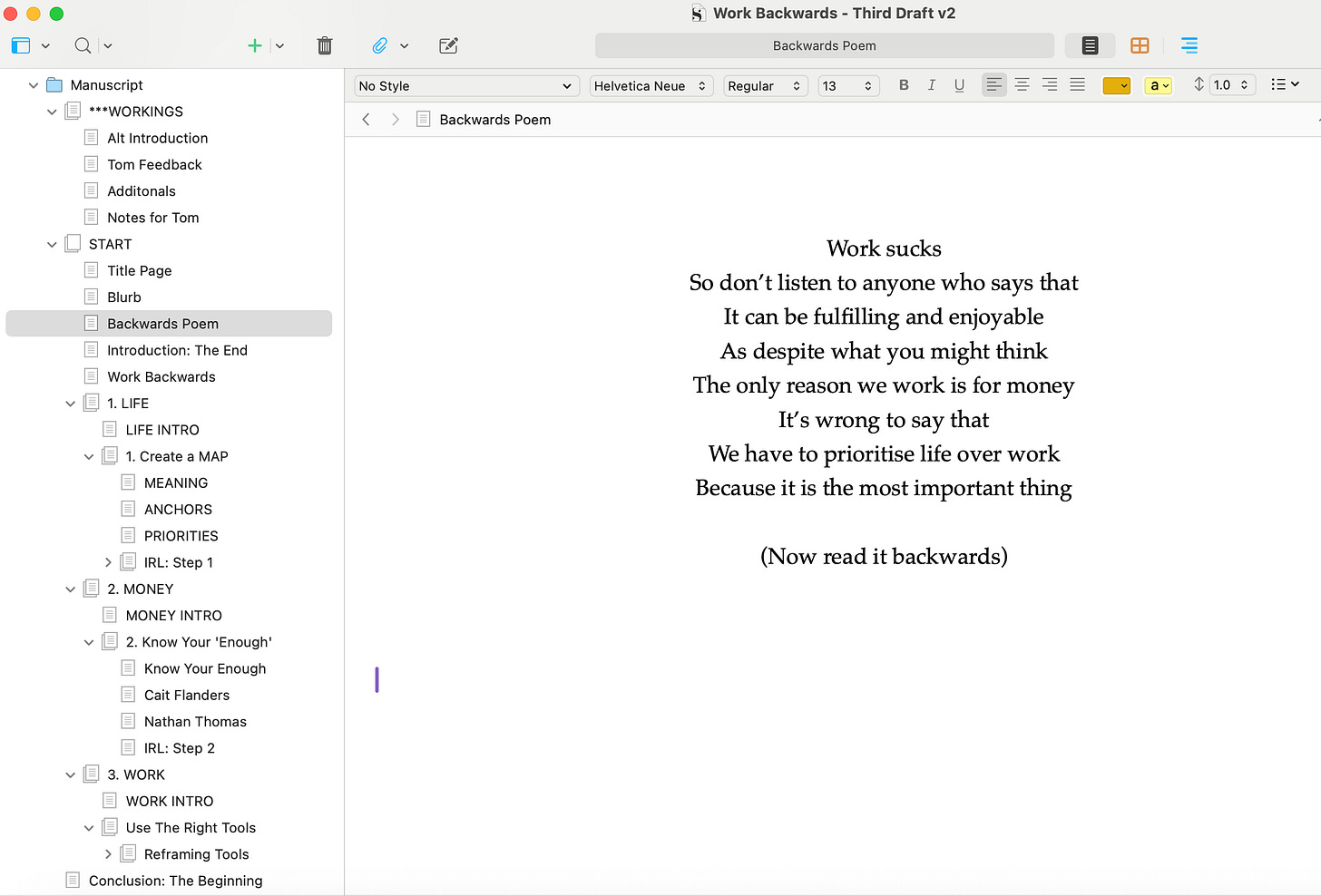

I use Scrivener for this, the excellent writing software, to write the actual words that end up in all my books. I love it for two main reasons.

One, it’s not Microsoft Word or Google Sheets, which I tend to associate with work and writing shorter form content like my weekly column. I use Scrivener for one purpose only, and that’s to write books. This means I can clearly and mentally switch into book writing time, without distractions, just by opening the program.

The second reason is that I have personalised it exactly how I like to write. To give you an example, this is what my Scrivener screen looked like for Work Backwards:

The left-hand column is where the magic happens.

Each of those tabs contains a small section of the book, and seeing it laid out like this means that I can easily see the bigger picture of how the book flows.

To change the order of certain sections I just drag and rearrange entire sections of the book without having to scroll up and down on Microsoft Word or Google Docs (ugh).

My process to move from Collect to Collate is that once each Note is full I transfer it (ie ‘Book 3.1’ and ‘Book 3.2’) into Scrivener, going through each line one-by-one. I interrogate them thoroughly, click on the links, read them properly and combine them together. When I’ve finished with a thought I bold it so I know that I’ve dealt with it.

This what it looks like:

It’s a simple system, and I repeat it over and over and over, creating and discarding.

Scrivener is the program I love clicking on the most on my computer. If you want to test it out, you can trial it for free and buy it here using my affiliate link (thank you in advance!).

Step 3: Expand

The best ideas from this step are then expanded upon. This might involve speaking to an expert, fleshing it out with a few paragraphs of words, or pulling the most useful statistic from some research.

I remember my first editor, Lex Hirst, once described the process of book writing like creating a mosaic artwork. My job as the writer is to describe the beautiful scene people will see once all the mosaics are arranged together, and then to explain each of the tiles as I slowly zoom out so they can see the whole picture.

I love that analogy, and still think about it as I write each book. Every one of these ideas is a small section, a tile, of a greater artwork, the mosaic.

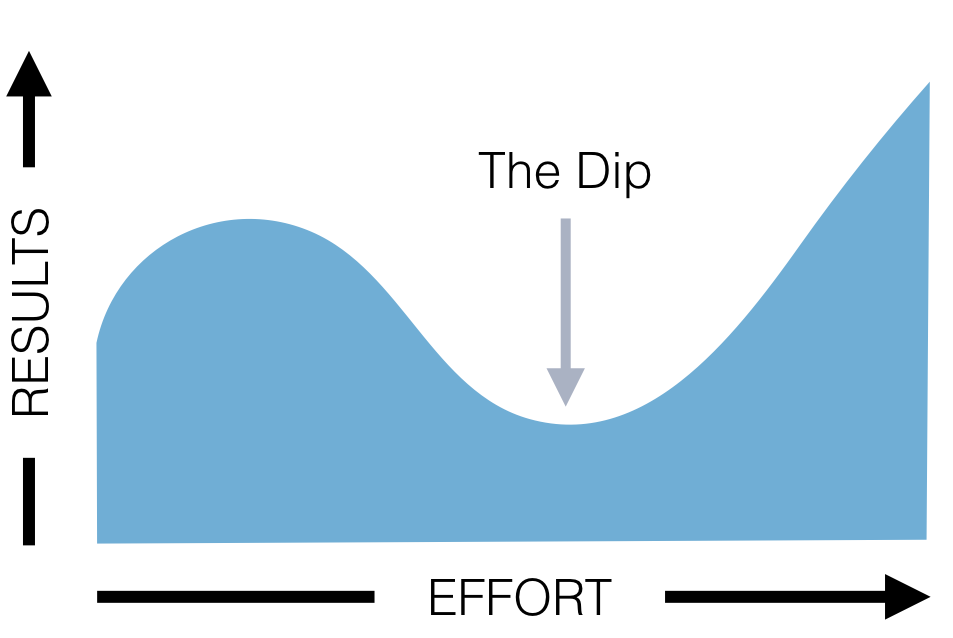

This part of the process, expanding the ideas into something that’s greater than a sum of its parts, is the hardest part of book writing. It’s when it sometimes feels like you’re trying to walk through quicksand, and I’m often reminded of The Dip by Seth Godin, that I’ve written about before.

Step 4: Order

The final step, and a real art, is arranging it. I usually am too tricky with my structure on the first drafts, before being pulled back into more classical structure by my editors.

The simplest advice is to tell your reader what you’re going to say, say it, then tell them what you said. A reader wants to know where they are in a book, how long they have to go, and how they can apply it. That’s why so many of my books have followed easy “7 step” or similar structures.

This process normally takes me around 1 to 2 years to get through (yep!), and it’s not always linear. It’s difficult and illuminating in equal measures to write a book, and I have immense respect for anyone else who’s able to find their way through it.

But it all begins with a simple thought that gets collected, then collated, then expanded and arranged. Eventually all that work ends up as a book that you welcome into your homes and heads one day in the future.

And that’s the best feeling in the world.

I’m currently collecting, collating, expanding and arranging ideas for my new book as I move around the Greek Islands. We are spending a week at a time on some of the most interesting ones in the Cyclades: Folegandros, Sifnos, Serifos and Tinos. It’s as lovely as it sounds. There is nothing and everything to do.

However, at the end of this month I’m heading back to Australia. I’ll be in Perth to speak at the excellent State of Social conference, then in Sydney and Melbourne to host some more events.

I’m also currently working on a very exciting annual mentorship program that I’m going to be announcing right here next month. If you’ve got something in the back of your mind that you want to achieve in 2025 (no matter how big or small) and need some guidance, skills and accountability to ensure that you do it, then this one’s for you.

Yours in usefulness,

Tim

Mate, this is like you opened the fridge door of my brain, saw what was missing, and went and stocked it. Thank you.

Saved for when I finally dive into writing my first book. Hopeful connect with an aligned agent soon to begin the journey. Thanks for this breakdown, and enjoy Greece!